First we need to understand what this statistical shift signifies. Is what we are seeing a mass exodus of true believers from the church? A large-scale apostasy? I'd wager not. The fact is, the statistics show that 48% of America still self-identifies as Protestant. If that number doesn't seem outright laughable, you have a poor definition of what Protestant means. Nowhere near even that many are. It used to be (and for quite a few Americans still is) that to be born in the USA is to be a Protestant. There was a time when you couldn't get a bank loan without membership at a church, or at the very least a synagogue. (Did we really think that policy was bound to make sincere and deep Christians?) Wikipedia defines a Protestant as a member in "any of several church denominations denying the universal authority of the Pope and affirming the Reformation principles of justification by faith alone, the priesthood of all believers, and the primacy of the Bible as the only source of revealed truth." Do we really think that even close to 48% of the population of the country believe these things (with exception to the point about the pope ;)? It would be wonderful, but such is not the case.

So what's happening is NOT a decline of real, Protestant believers, but a purging of nominal Christians. This statistical decline depicts not the death of the church, but rather of Christendom: a society-wide structure based on some generic Christian values in which everyone considers themselves Christian by default, simply because they were born into the system. But the reality is there are no default Christians! You don't get to call yourself a Protestant just because you were born in America and hold some vaguely Christians understandings, the same way you don't get to call yourself a fish just because you were born in the bathtub and like to swim on vacation. The issue is that in America, the default religion is Protestantism, the same way that in Italy it's Catholicism (88%) or in Ukraine it's Eastern Orthodoxy (around 70%). But the truth is that in none of these countries does even a fraction of the population actually and sincerely believe in the teachings of its particular default religion. That is, they are nominal - believers in name only. So what is responsible for this trend in America?

One commentary on the new statistics from the linked article lays it out this way:

"'Part of what's going on here is that the stigma associated with not being part of any religious community has declined,' said John Green, a specialist in religion and politics at the University of Akron, who advised Pew on the survey. 'In some parts of the country, there is still a stigma. But overall, it's not the way it used to be.'"In other words, now that you don't need to be a member of a church to get a bank loan, the people who were in the church only for superficial reasons linked with Christendom are leaving. Nominal Christians no longer have to keep up the pretense because the belief that to be a decent American means you must go to church on Sunday has all but disappeared. What that inevitably means is that, while the numbers of people who call themselves Protestant may be declining, the number of real believers is not. In fact, there are at least two reasons why this trend is positive.

First, this presents an exciting opportunity to share the Gospel. There is practically no one harder to share the Gospel with than someone who thinks they already know it but doesn't; with someone who thinks they are already a Christian but they aren't. At least when someone says they are not a Christian or believe in "nothing in particular", there is a possibility of an honest dialogue. But it is often much harder to tell someone who thinks he's a Christian that he needs to become a Christian. I would personally much rather have a conversation with someone who recognizes Christianity and the Gospel as something they don't currently believe and is willing to debate it with me than try to convince someone who is simply putting on the Christian show that they are not actually a Christian. History bears out this sharp and honest distinction as beneficial. It was the prostitutes and thieving tax collectors who came to Jesus, not the Pharisees who thought they were already good to go. It was, ultimately and generally speaking, the Gentiles of places like Corinth that were more open to Paul's message than the population of Jerusalem (though there were certainly not a few of the Jewish people who came to faith as well.) Even in our own days, the growth rate of the Evangelical church is highest in countries that are NOT part of the Christendom structure. Of course, the residual problem in America is that many of even those who no longer affiliate with the Protestant church think they know what the Gospel is. Therefore, the exodus of nominal Christians from the church is not a panacea to this problem, but at least they aren't lying to themselves anymore about believing it, and that's a step in the right direction.

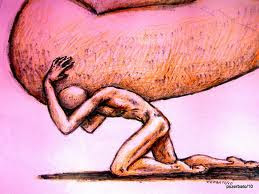

The second reason we should be glad for this change is that, ultimately, this trend will beautify the church. If those who are not serious about faith in Christ, those who were Protestant in name only or were so out of a vague sense of patriotic affiliation leave the church, that means that the people who stay will be more and more those who truly love Jesus and want to worship Him with their lives. Granted, there will still be plenty of nominal Christians in the church unless some kind of serious persecution begins, but nevertheless, the trend of the church being pruned of dead branches will ultimately lead to a greater vibrancy, attractiveness to those outside, and therefore fruitfulness. Pruning might be painful, but it is a reason for hope, not for despair. It is a condition of life, not a mark of death. It seems to me the reason that many Christians begin to panic over these statistics is that we, in a stereotypical super-size mentality, often confuse quantity with quality and think that bigger numbers must necessarily mean the church is better off when this is very contradictory to the biblical picture. In fact, the stated preference of God in Scripture is that people who come in vain would do better to stop pretending and just not come (Mal. 1:10 and Rev. 3:15-16 come to mind.)

So though the pruning process might not be fun, might entail some real pain for churches and truly require us to adapt in order to be witnesses in a "post-Christian" society, the truth is that society was never "Christian" in the first place, only "Christianized" and that this change is ultimately not something to fear or cause despair, but to applaud, because ultimately it just means that people are finally getting honest with themselves and others and that's something we should all be able to agree is a good thing.