thoughts on life, culture, politics, ministry, the church, our family and just about anything else and how it all ties in to Jesus

Wednesday, July 11, 2012

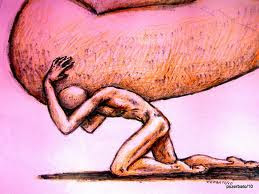

social justice in the church: the necessity and the danger

Recently I've been hearing (and reading) lots of people take strong stances on the question of social justice in the life of the church. These opinions are as varied as "if you're not actively participating in programs to serve the poor and marginalized, you're a horrible Christian", to "social justice is not the calling of the church and is a distraction from the Great Commission."

As for the idea of social justice being a distraction from the church's true calling, this just doesn't seem like a serious argument to me, or one with any biblical foundation anyway. It really only requires taking a look at perhaps the one Christian who fulfilled the Great Commission like no other: the Apostle Paul. When Paul went to Jerusalem to tell the other Apostles about how God had been working salvation among the Gentiles through him, fulfilling the Great Commission in an unprecedented way, their reply was that they "perceived the grace that was given to me, they gave the right hand of fellowship to Barnabas and me, that we should go to the Gentiles and they to the circumcised. Only, they asked us to remember the poor, the very thing I was eager to do." (Gal. 2:9-10) Far from being a distraction from the Great Commission, the early church and Paul himself looked on issues of social justice as inseparable from the Great Commission. Their encouragement to Paul is not "make sure you don't let anything distract you from that, Paul", but rather that social justice MUST be part of the Great Commission. Can anyone really read the epistle of James or 1st John and doubt the importance of social justice in the life of the believer? I'm not going to attempt a full, theological justification of the necessity of social justice ministry in the church in this blog post. If anyone is in need of convincing, I'd simply recommend reading Generous Justice, by Tim Keller.

However, I do believe there is a potential danger in the recent awakening to social justice. That danger is not in the recognition of the need for justice, nor in our call to pursue it, but rather in the motives and goals we hold behind the pursuit. It is no coincidence that the majority of the noise surrounding the church's call to social justice is coming from developed countries where there is a justice system in tact. In the rare (read "western") corners of the world where justice is the accepted standard of society, there is a subtle temptation to import the value of justice from society at large into the church, without examining its form and source.

If the ardor behind our pursuit of justice is the expectation of establishing a just system rather than out of love of our neighbor and to manifest the nature of the coming kingdom, we will burn out and not really be fulfilling the biblical call to social justice. In other words, there is a danger of seeing ourselves as the fountainhead of justice rather than waiting expectantly for the returning Judge. Western society, where this renewed call to social justice in the church is strongest, generally supports the value of justice for the individual (compared with the rest of the world anyway). But has the growing cause of justice in secular society been born from spiritual insight into the character of God? Is it not more likely the result of abandoning any belief in ultimate, eternal justice and hence there arises our need to create our own justice here and now? And therein is the danger: that as the church pursues justice she will do so in a way no differently from society at large. She will merely mimic the secular pursuit of justice. The danger is that our pursuit of justice ceases to be a manifestation of love to our neighbor and a sign of the coming kingdom of Christ, and rather flows from a desire to control our circumstances, to mitigate our own suffering in the world, and from a lack of real belief in the ultimate justice of the Judge of the living and dead. The truth is that our pursuit of justice can flow just as much from a lack of faith in the coming justice of God as it can from our obedience to the Judge and in conformation to His character.

The church is called to social justice, but we must understand why and from what motive. The church is called to transformation into Christ's image and to love our neighbor, therefore social justice is not an optional activity for the Christian. See, we can hardly pretend to be loving our neighbor if we are indifferent to his suffering (though many do). This is the whole point of John's rhetorical question in his first epistle: "But if anyone has the world's goods and sees his brother in need, yet closes his heart against him, how does God's love abide in him?" (1 Jn. 3:17) John goes on to make the point that anyone who doesn't love his brother but says he loves God is a liar. Therefore, it's true that if we neglect questions of social justice and shut up our hearts from others' suffering, we ARE horrible Christians. But we must be sure that the motives behind our pursuit of justice are namely these: that we pursue social justice out of love for our neighbor, because God loves him or her and calls us to be conformed to His image. We do so not in expectation that we as the church will be capable of creating perfect conditions where justice flourishes. In fact, our attempts may not actually change the structures of justice at all. Another way of saying this is that we pursue social justice as a manifestation of love, as a reflection of the kingdom of God in which Jesus will establish complete and ultimate justice. We must not forget that we, as believers in Christ, though being the firstfruits of the inaugurated kingdom of God, are not currently in the fully realized version of that kingdom. Neither is it through our efforts that this realization will come about, but through the return of the King to establish His kingdom.

I have lived the last 10 years of my life in a country that lacks a just society (at least compared with North America or Western Europe). Sons of millionaries and members of parliament rape and pillage (literally) whatever and whoever they want and are rarely called to account for it. Workers in factories labor in conditions that would be considered animal cruelty in the west. The honest are few and far between and usually suffer for their integrity. Even rarer are those who would step up to defend the helpless for fear that they would be the ones to bear the blame (and history has often justified this fear.) Corruption among those who are supposed to uphold justice is so pervasive that people openly joke about it. (One of those "we laugh so we don't cry" kind of things.) The government is interested primarily in stuffing its own pockets rather than caring for the welfare of its citizens. And it is in that context that I am called to seek justice for my neighbors as a manifestation of love. What must be the goal? If the calling is the creation of a just society by my efforts (or even those of the church at large), there is cause for despair. But if the calling is to come along side the victims, the oppressed, the marginalized and take their suffering as my own and to work to the extent of my ability to serve their tangible needs as a reflection of the coming kingdom where this will be realized, that pursuit of justice can be a true act of love regardless of the outcome. Sometimes this pursuit yields results (my clout as one of only 2 Americans in the city does tend to improve the attitudes of the government employees I've had to deal with in seeking to serve others, and I am grateful for God's providence in that), but mostly not. The danger of the pursuit of social justice as a goal in itself becomes very clear, very quickly. In the framework of corruption and abuse of power, "justice" as an end in itself may never be achieved. However, justice as a manifestation of compassion, empathy and love will not be diminished or frustrated by its practical results. We must see that coming along side to take the suffering of the oppressed and marginalized on ourselves is already a victory as it manifests the love of the God who came to bear our suffering, regardless of if temporal justice is served or not.

thoughts?

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

4 comments:

Ben,

Good thoughts. I recently read a book on the topic of justice by a Harvard professor named Michael Sandel called "Justice". As I read it I thought of you as it dealt not so much with what justice is but the underlying value/thought systems that various people and societies have that affect what we think is just. Really helpful in working through the American mindset of justice as well as having to think critically about whether or not our vies are biblical or cultural. If you are ever in my neck of the woods you can borrow it.

thanks, danny. i had actually heard of sandel's harvard course on justice a while back (while watching colbert interview him. ;) not sure if you're aware, but you can view his lectures from the course online: http://www.justiceharvard.org i haven't watched them, but i think i might just have to do that now.

on a related note, i've actually been in a protracted fb debate with a friend of mine who is an atheist, utilitarian, and philosophy of mind student working on his masters, about the problem of ethics without a divine source. if you are interested in reading it (and i think you should be able to, since you are in my friends list, you can find it here. the reason i bring it up is because his attempts at "ethical dilemmas" in the beginning of our debate mirror sandel's examples. but there is a much more basic question that must first be answered: where do ethics come from?

Ben,

Yeah, you should watch the lectures. In the book he tries to show from history how different philosophers have dealt with the question of what to base ethics on without a divine standard and I think it is helpful for discussions like you are describing.

Danny

Post a Comment